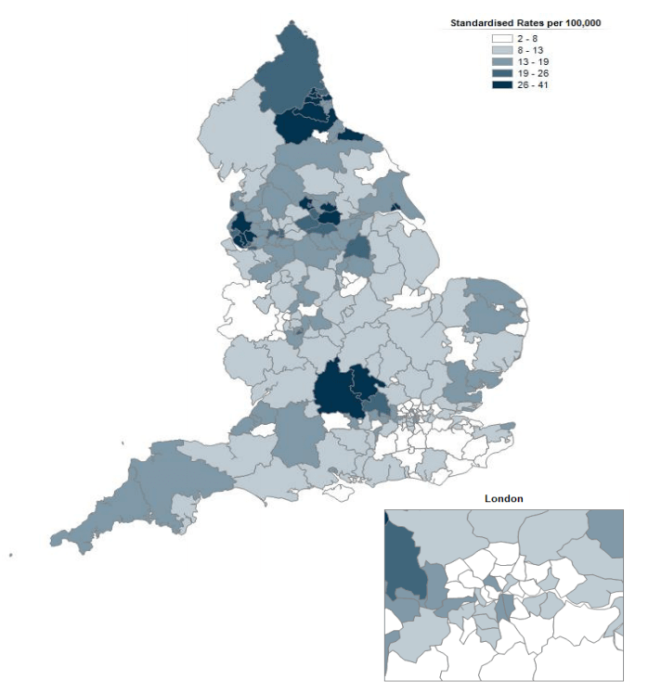

The NHS Digital figures show that dog bite-related hospital admissions increased by 6.5% from 2013-2014 period (Fig. 1). In May 2015, Merseyside was named “the dog attack capital of Britain” after 322 dog bite victims needed treatment between March 2014 and February 2015 (Taylor, 2015). These statistics are concerning but they also illustrate another important point about dog bites: most research into dog bites is rooted within an epidemiological framework. Epidemiology studies patterns of diseases: how often they occur, to whom and why. Epidemiological studies of dog bites often include counting how many dog bites occur in a specific area, in what context, who are the victims and the dogs.

Fig. 1. Heat map of dog bites in the UK. The map shows hospital admission rates (per 100,000 population) for dog bites and strikes by Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) of residence and corresponds to the period between 8th March 2014 to February 2015. Source: Winter (2015)

However, the perception of dogs in the Western societies is changing — dogs are commonly seen as family members, we buy them birthday gifts and outfits for special occasions (Holbrook & Woodside). For this reason, we need to understand dog bites as a social problem and not just a medical one and study them from a social perspective.

In my PhD research, I hope to explore what are the perceptions of dog bites and how they shape people’s interactions with dogs to understand how to best prevent them. To illustrate why this is important, let’s look at this made up scenario:

Fido (the dog) is scared of fireworks and as it’s the end of December, you can hear loud bangs throughout the day. His owner’s family are still around and a few days of playing with children and no proper walks left Fido feeling tired and anxious. Frank (the victim) met Fido in the park previously and on Wednesday morning, he saw Fido again, tied to a railing in front of a local shop. He petted the dog in the park a few days ago, so this time he came forwards with confidence to pet the dog again. As he leaned towards the Fido, the dog bit his face. Frank was shocked– he has met Fido just a few days ago and the dog was fine with him! He didn’t think a bit would ever happen to him, dogs always like him! When John, the owner, came out of the shop he couldn’t believe his dog did that. He was always fine being tied in front of the shop, even when approached by kids!

As a result of the bite, Frank has significant scaring to his face. He rarely goes out or socialises with friends. John is really upset about what has happened too- he still doesn’t understand how his beloved dog could have done it. He stopped walking Fido regularly, worried that a dog may bite again and always locks him in a spare room when he has visitors. His grandchildren come over less often and John feels more isolated. Fido is really distressed whenever he is left locked on his own away from John and struggles to cope too.

Although this scenario isn’t real, it illustrates how dog bites can be seen from a social perspective- their consequences to dog bite victims, dog owners and dogs reach further than the physical wounds and can seriously affect welfare and wellbeing of people and dogs. Social factors- like our relations with family and friends and a broader cultural context can shape our interactions with dogs, and though this, our risk of being bitten. For instance, Frank might have behaved differently if he was walking with his 4-year-old daughter- the consideration of this social relationship might have changed how he came up to the dog. Meeting a dog during holidays in Mexico, where not all dogs are pets could have also influenced his actions. We can only speculate how the interaction would be different if he didn’t meet Fido a few days before the accident. Would he act differently if his family didn’t keep dogs and he didn’t think of himself as being good with dogs? Would the interaction end differently if it took place after Christmas when Fido was less anxious and less often scared by the fireworks? Would John tie Fido outside of the shop if he had less trust in his dog’s behaviour? Would he cope with the aftermath of the bite better if he didn’t live on his own?

Very little is still known about how people see dog bites and how they make daily, practical decisions that may impact on theirs and others safety around dogs. A previous study showed, for instance, that people who had dogs of a particular breed are less influenced by breed related stereotypes and may approach such dog differently to people who never had a dog of this type (Clarke, Cooper, & Mills, 2013). A study where dog bite victims were interviewed illustrated that victims (who were also often the dog owners) frequently think that a bite “wouldn’t happen to them”, which may influence their behaviour around dogs and what, if anything, do they do to prevent bites (Westgarth & Watkins, 2015). The person’s prior experience with dogs, knowledge about dog behaviour, and their perceptions of dogs, dog bites, risk and safety, in general, have a capacity to influence what they do when they meet a dog. Dog’s prior experiences with people, how they were socialised as puppies and the training they received will shape their interactions, just as much as more immediate factors, like fireworks that many dogs are fearful of (Blackwell, Bradshaw, & Casey, 2013), or lack of possibilities to escape (due to being tied up).

In my PhD research, I hope to interview dog bite victims and dog owners to explore what may affect their perceptions of dogs and dog bites and how these may influence their behaviour around dogs. I hope that by understanding these aspects of human-dog interactions, we will be able to revise bite prevention campaigns to take into account the social dimension of dog bites.

Blackwell, E. J., Bradshaw, J. W. S., & Casey, R. A. (2013). Fear responses to noises in domestic dogs: Prevalence, risk factors and co-occurrence with other fear related behaviour. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 145(1-2), 15-25. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2012.12.004

Clark, T., Cooper, J., & Mills, D. (2013). Acculturation: perceptions of breed differences in the behavior of the dog (Canis familiaris). Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin, 1(2), 16-33.

Holbrook, M. B., & Woodside, A. G. (2008) Animal companions, consumption experiences, and the marketing of pets: Transcending boundaries in the animal-human distinction. Journal of Business Research, 61(5), 377-381.

Taylor, J. (2015, 28/05/2015). Merseyside named dog attack capital of Britain after surge in hosptial admissions. Liverpool Echo. Retrieved from http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/merseyside-named-dog-attack-capital-9350595

Westgarth, C., Watkins., F. (2015) A qualitative investigation of the perceptions of female dog bites victims and implications for the prevention of dog bites. Journal of Veterinary Behaviour, 10(6), 479-488.

One thought on “Barking up the wrong tree”